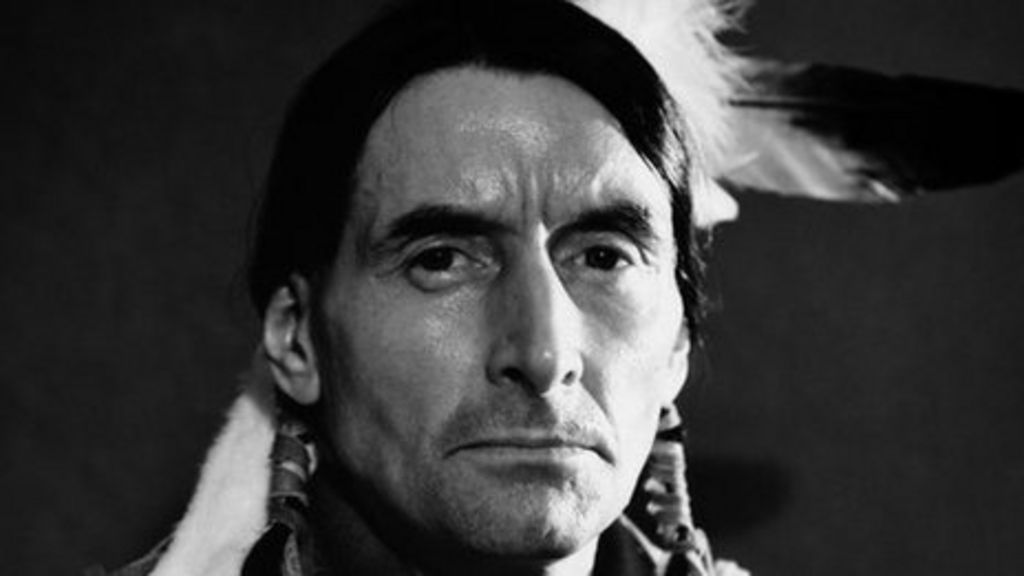

Grey Owl is a 1999 biopic directed by Richard Attenborough and starring Pierce Brosnan in the role of real-life British schoolboy turned Native American trapper 'Grey Owl', Archibald Belaney (1888–1938), and Annie Galipeau as his wife Anahareo, with brief appearances by Graham Greene and others. Home Video Trailer from Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. Grey Owl (1999) PG-13 Biography, Drama, Western.

Climbing the ancient Mayan ruins of El Mirador, Tikal and Yaxha in northern Guatemala and trekking through the jungles of the mysterious Darien Gap on Panama’s border with Colombia in search of a giant eagle... British wildlife TV presenter Nigel Marven is doing it all and taking the audience on an exciting journey to Central America, exploring its diverse wildlife and colourful culture. Get up close with colourful quetzals in Honduras, frog-eating bats in Panama, feisty reptiles and lava-spewing volcanoes in Guatemala as Nigel travels in search of special animals and uncovering lost cities and their cultures on Wild Central America, airing every Monday on Animal Planet at 10pm and streaming on Discovery Plus app.

You describe yourself in your Twitter bio as a “time-travelling zoologist who was chased by dinosaurs”. Why?

Time-travelling zoologist, because in my most famous shows Sea Monsters and Prehistoric Park, with the help of state-of-the-art CGI I travelled back into prehistory to meet T- Rex and Tanystopheus (a long-necked sea reptile) mammoths and Microraptor (a small gliding dinosaur with feathers) and many more extinct creatures.

If time travel was really possible and if the animal kingdom of the respective age was to be the only consideration, which age would you want to do your shows in and why?

I’d travel back just 1,000 years to New Zealand before humans wiped out moas or elephant birds, the biggest of which were 2m tall. They were preyed upon by Haast’s eagle, the biggest eagle that’s ever lived. I met a harpy eagle in Panama for Wild Central America, so it would be brilliant to encounter an eagle weighing nearly twice as much.

Which countries are you covering in the show Wild Central America that’s airing here?

Honduras, Guatemala, Costa Rica and Panama.

Tell us about the most exciting encounter in each of the countries you cover.

The president of Honduras is a bird watcher. Seeing the Honduran Emerald in his garden was a highlight. Guatemala is a land of volcanos — hiking to within a kilometre of molten lava at night was brilliant. I’ll never forget seeing a harpy eagle take food to his chick in the Darien Gap, Panama. There’s fabulous frogs in Costa Rica. I loved meeting them.

One hears you have shot in India. When and where did you go? Did our animals treat you well?

I’ve filmed in India many times over the years. The temple of rats near Bikaner, Rajasthan, tigers in Bandhavgarh, sea kraits in the Andamans, lion-tailed macaques in Kerala and the Nagpanchmi cobra festival in Shirala. It’s always a great experience visiting India. As I don’t eat meat, the culinary experience is perfect too.

I really want to make a Wild India series, in the same style as Central America, for Animal Planet to boost eco-tourism in your country.

How did you become attracted to animals and birds? What kind of a childhood did you have?

I’ve loved animals for as long as I can remember, I never had train sets or toy cars, instead I raced walking sticks along the washing line and kept exotic pets, lizards and snakes.

You have worked with Sir David Attenborough. Any memorable experience you can share?

DA is a great communicator and ambassador to save our planet. My most memorable time with him was a long filming trip to the Galapagos. The lesson I learnt from him was that the animals are the stars of wildlife documentaries not the presenters.

You seem to have quite a menagerie at home. You have spoken about Diggers, the barn owl and Ninja, the giant gecko on Twitter. Has it been difficult to source their favourite food during the lockdown?

I have many exotic pets in my small home in Somerset, England. Digger is a free-flying burrowing owl, Misty a great grey owl. My snapping turtle lives in a big trough outside. In aquariums and enclosures inside I have a male Yemen chameleon, Miss Piggy, a Fly River turtle, Ninja, a giant New Caledonia gecko, hog nose, leopard, king mandarin and four lined snakes, as well as Giant African bullfrogs, axolotls and a Brazilian black tarantula. The food for the animals is sent by post, so no problems during the lockdown. I have a freezer full of frozen chicks, rats and mice. A box of crickets and locusts is delivered weekly.

All my animals are bred in captivity. None have been taken from the wild. As I’ve kept exotic pets since I was a boy I know how to keep them fit and healthy.

A cat has nine lives. How many does Nigel Marven have? Please share your scariest experiences.

My most frightening moment was when I was standing next to shark behaviourist Erich Ritter (who sadly died of natural causes recently); he was bitten in the leg by a bull shark (featured in one of Discovery’s biggest shows Anatomy of a Shark Bite). Usually the most perilous moments are driving to the locations. Before I meet animals I do a lot of research and ask experts how close I can get, then I take a calculated risk, but can still be surprised like when a deadly terciopelo struck and just missed me in Wild Honduras.

Grey Owl Casino Entertainment Ideas

Did Steve Irwin’s accidental death affect you? Did you alter your way of interacting with animals in the wild or at home after his death?

The brilliant Steve Irwin’s death was a freak accident, the sting rays tail pierced his heart, if it had hit him anywhere else he would not have died. In many places, tourists swim with sting rays. They’re not usually life threatening to people. Steve was just unlucky. His death has not affected my approach to getting close to dangerous animals, I always research their behaviours.

Grey Owl Casino Entertainment Console

Of all the species you have shot with, which would you vote for as your favourite and why?

Grey Owl Casino Entertainment Packages

A difficult question because I love them all. But watch out for white tent-making bats in Wild Costa Rica, mythical resplendent quetzals in Wild Honduras, the venomous beaded lizard in Wild Guatemala and the feeding manatees in Wild Panama. When I film in India I can’t wait for my first encounter with sloth bears and Asiatic lions.

Did you film this year?

This is the first year of my professional life when I haven’t filmed abroad. I’m itching to travel again when the pandemic is under control

Grey Owl Casino Entertainment Center

| Film Studio | |

| Industry | |

|---|---|

| Fate | Assets sold to InterMedia |

| Founded | 1989 |

| Founder | Lawrence Gordon |

| Defunct | 1999 |

| Headquarters | |

| Owner | JVC |

Largo Entertainment was a production company founded in 1989. It was run by film producer Lawrence Gordon and was backed by electronics firm Victor Company of Japan, Ltd. (JVC) in an investment that cost more than $100 million. The production company released their first film, Point Break in 1991 and their last film was Grey Owl in 1999.

History[edit]

In August 1989, Gordon formed Largo Entertainment with the backing of JVC, representing the first major Japanese investment in the entertainment industry. Although JVC put up the entire $100 million investment, the company was structured to be a 50/50 joint venture between Gordon and JVC.[1] As the company's chairman and chief executive officer, Gordon was responsible for the production of such films as Point Break (1991), starring Patrick Swayze and Keanu Reeves; The Super (1991), starring Joe Pesci; Unlawful Entry (1992), starring Kurt Russell, Ray Liotta and Madeleine Stowe; Used People (1992), starring Shirley MacLaine, Jessica Tandy, Kathy Bates, Marcia Gay Harden and Marcello Mastroianni; and Timecop (1994), starring Jean-Claude Van Damme. Largo also co-financed and handled the foreign distribution of the acclaimed 1992 biopic Malcolm X, directed by Spike Lee and starring Denzel Washington in the title role. In January 1994, Gordon left the company and forged a production deal at Universal.[2] In 1999, JVC transferred Largo's film acquisition assets to JVC Entertainment, a film subsidiary for the Japanese market, and shut down its foreign sales operation.[3] Largo's film library was acquired by InterMedia in 2001.[4]

Filmography[edit]

| Release Date | Title | Distributor | Notes | Budget | Gross (worldwide) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 12, 1991 | Point Break | 20th Century Fox | co-production with Tapestry Films and Johnny Utah Productions | $24 million | $83.5 million |

| October 4, 1991 | The Super | co-production with Daybreak Productions | $22 million | $11 million | |

| June 26, 1992 | Unlawful Entry | $23 million | $57.1 million | ||

| October 23, 1992 | Dr. Giggles | Universal Pictures | co-production with Dark Horse Entertainment | N/A | $8.4 million |

| November 18, 1992 | Malcolm X | Warner Bros. Pictures | co-production with 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks | $35 million | $48.2 million |

| December 16, 1992 | Used People | 20th Century Fox | $16 million | $28 million | |

| October 15, 1993 | Judgment Night | Universal Pictures | $21 million | $12.1 million | |

| February 11, 1994 | The Getaway | N/A | $30 million | ||

| September 16, 1994 | Timecop | co-production with Signature Pictures, Renaissance Pictures and Dark Horse Entertainment | $27 million | $101.6 million | |

| February 2, 1996 | White Squall | Buena Vista Pictures | co-production with Hollywood Pictures and Scott Free Productions; also international distribution rights | $38 million | $10.2 million |

| April 26, 1996 | Mulholland Falls | MGM/UA Distribution Co. | co-production with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures, The Zanuck Company and PolyGram Filmed Entertainment | $29 million | $11.5 million |

| October 9, 1996 | The Proprietor | Warner Bros. | co-production with Merchant Ivory Productions, Ognon Pictures and Fez Production Filmcilik | N/A | |

| November 29, 1996 | Adrenalin: Fear the Rush | Legacy Releasing Corporation | co-production with Filmwerks and Toga Productions; distributed to home video by Buena Vista Home Video and Dimension Films | N/A | $37,536 |

| January 31, 1997 | Meet Wally Sparks | Trimark Pictures | co-production with The Greif Company | $4.1 million | |

| March 14, 1997 | City of Industry | Orion Pictures | $8 million | $1.5 million | |

| April 19, 1997 | Habitat | Sci-Fi Channel | made-for television film; co-production with Transfilm, Kingsborough Pictures, Ecotopia B.V. and August Entertainment | N/A | |

| July 8, 1997 | Omega Doom | Columbia TriStar Home Video | direct-to-video; co-production with Filmwerks | ||

| July 11, 1997 | This World, Then the Fireworks | Orion Pictures | co-production with Balzac's Shirt, Muse Productions and Wynard | N/A | $51,618 |

| July 25, 1997 | Box of Moonlight | Box of Moonlight Picture Corporation | co-production with Lakeshore Entertainment and Lemon Sky Productions | $782,641 | |

| August 22, 1997 | G.I. Jane | Buena Vista Pictures | co-production with Hollywood Pictures, Caravan Pictures, Roger Birnbaum Productions and Scott Free Productions | $50 million | $48.1 million |

| February 27, 1998 | Kissing a Fool | Universal Pictures | co-production with Rick Lashbrook Films | $19 million | $4.1 million |

| April 9, 1998 | Shadow of Doubt | New City Releasing | N/A | ||

| October 30, 1998 | Vampires | Sony Pictures Releasing | co-production with Columbia Pictures, Storm King Productions, Film Office and Spooky Tooth Productions | $20 million | $20.3 million |

| December 30, 1998 | Affliction | Lions Gate Films | co-production with Kingsgate Films | $6 million | $6.3 million |

| May 21, 1999 | Finding Graceland | Columbia TriStar Home VIdeo | direct-to-video; co-production with TCB Productions and Avenue Pictures | N/A | |

| November 9, 1999 | Bad Day on the Block | direct-to-video, co-production with Sheen/Michaels Entertainment | |||

| February 15, 2000 | Grey Owl | direct-to-video; co-production with Allied Filmmakers | $30 million | $632,617 | |

References[edit]

- ^EASTON, NINA J. (1989-08-21). 'Japanese Firm in $100-Million Hollywood Deal'. Los Angeles Times. ISSN0458-3035. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- ^O'Steen, Kathleen (1994-01-13). 'Gordon leaves Largo'. Variety. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- ^Roman, Monica (1999-02-08). 'JVC to forgo Largo'. Variety. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

- ^Dawtrey, Adam (2001-03-14). 'Largo library to Intermedia'. Variety. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

External links[edit]

- Largo Entertainment on IMDb